UNIVERSITY OF ABERDEEN

CENTRE FOR CONTINUING EDUCATION

NORTH-EAST STUDIES

1997 - 1998

LOCAL HISTORY DISSERTATION

FROM THE WILDERNESS TO PARADISE

A STUDY OF THE DEVELOPMENT OF AGRICULTURE

IN THE PARISH OF KEMNAY

1750 - 1870

DUNCAN A DOWNIE

INTRODUCTION

The purpose of this dissertation is to trace the development of agriculture/arboriculture in the parish of Kemnay from the 1750s to 1860s examining farming practices, changes in land use and assessing the changes on the estate during the period.

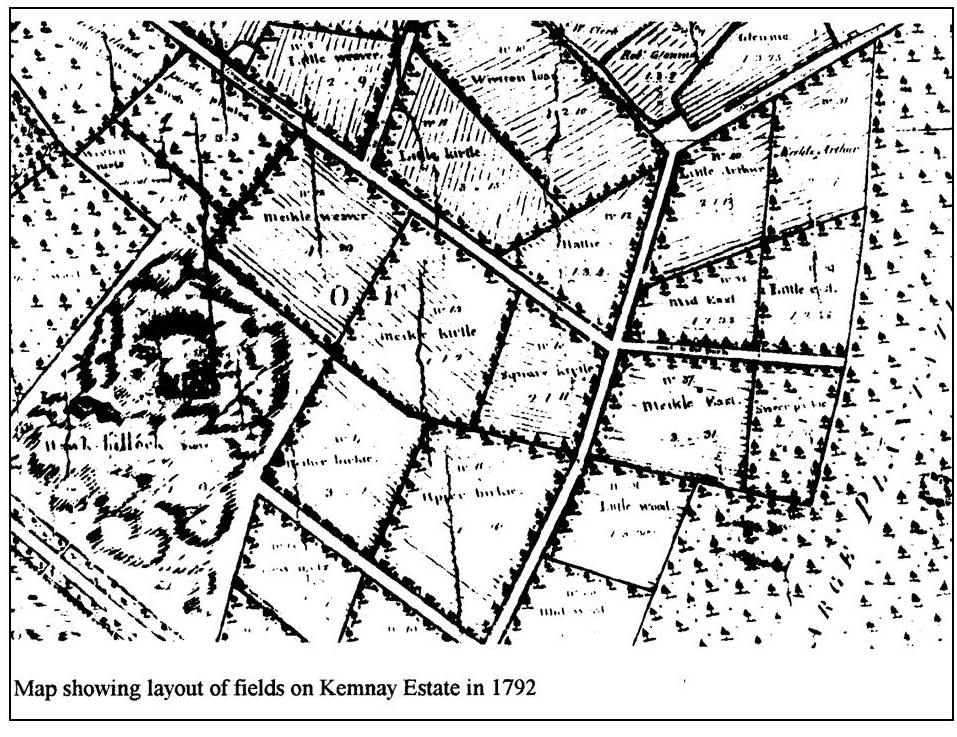

The major area of research was in the Burnett Archive [NRA(S) 1368] in Kemnay House, a hitherto untapped source of material. These contain, amongst other things, an estate map of 1792 which gives a detailed layout of the estate and gives the tenants' names to the holdings. There are various other maps and a number of bundles of family correspondence.

Relative to the present research are two bundles of letters from the gardener-cum- overseer, to the laird, John Burnett, who was resident outwith the estate. The first of these was Alexander Winehouse whose letters exist between 1808 and 1815 and the second was James MacAllan, his successor, whose letters for the period between 1824 and 1841 survive. These two files of correspondence contain income and expenditure accounts to the laird and also give happenings on the estate and sometimes requests for directions from him. Through these letters the writer has been able to gather a picture of life on the estate during that period, and names encountered over the years in previous research have now become people going about their daily living.

Other records used have been local Kirk Session Records which show how the kirk was responsible for the poor in the parish and the efforts made by the Session along with the heritors [landowners] to cushion the less well off in the parish from hardship.

Census returns exist from 1801 to 1891, but early censuses do not give much information. Use has been made of the censuses from 1841 to 1861. The 1841 census provides little information other than the names of the people and place of residence. Ages were usually rounded to the nearest five, making it less dependable than later census documents.

The first statistical account was prepared for each parish in Scotland in the 1790s under the direction of Sir John Sinclair. The reports were usually prepared by the minister of the parish under various headings and topics. The second account was prepared during the late 1830s and early 1840s. Kemnay was one of the few parishes where the same writer, Rev Patrick Mitchell, prepared both accounts. Unfortunately, for us, he did not elaborate too much on the headings, which makes the reports somewhat short and less informative than those of other writers. The third statistical account was prepared after the Second World War.

The whole country was surveyed during the 1860s and maps were prepared and issued by the Ordnance Survey Office in Southampton. They were produced to various scales and those consulted were 1:2500, 1:10560 and 1:63360. These give a very detailed picture of the area at the time and show the development of building and enclosures.

Occasional reference has been made to other sources as indicated in the text and in the bibliography.

DESCRIPTION OF AREA OF RESEARCH

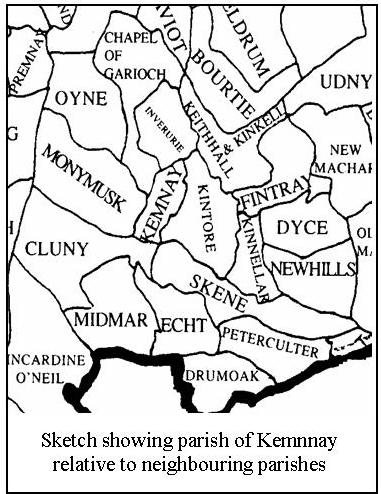

The parish of Kemnay is situated in central Aberdeenshire some fifteen miles north west of the city of Aberdeen. Its land area is 5113 acres and compared with the neighbouring parishes it is relatively small in area: Cluny 10045 acres, Monymusk 10728 acres, Chapel of Garioch 13060 acres, Inverurie 4948 acres, Kintore 9098 acres, Skene 10247 acres [Statistical Account of Scotland (1791 – 1799) Vol. XIV - parish reports].

The parish of Kemnay is situated in central Aberdeenshire some fifteen miles north west of the city of Aberdeen. Its land area is 5113 acres and compared with the neighbouring parishes it is relatively small in area: Cluny 10045 acres, Monymusk 10728 acres, Chapel of Garioch 13060 acres, Inverurie 4948 acres, Kintore 9098 acres, Skene 10247 acres [Statistical Account of Scotland (1791 – 1799) Vol. XIV - parish reports].

At the time of the first statistical account (1792) the population was given as 611. The parish of Kemnay was at that time somewhat backward and barren. The only trees in the whole parish were those which had been planted some forty years earlier by the laird. According to the survey carried out in 1792, there were some 1330 acres of arable land, 253 acres of pasture, 160 acres of woodland, 212 acres of moss and 1350 acres of rough ground and moor. The ground was of a rather poor nature, but one curious fact emerged that:

'The ground on top of Paradise (hill) and all round the summit for some distance down on every side, is an excellent soil, but gradually becomes of an inferior quality as you approach the bottom.' [Statistical Account of Scotland (1791 – 1799) Vol. XIV p.537]

It has long been believed that the parish derived its name from the long trail of eskers (glacial remains) known locally as kembs or kaims which stretched across the centre of the parish from the Cluny border past Craigearn and terminating near Dalmadilly. Johnston [Johnston James B., Place Names of Scotland (1970)] suggests that it is derived from the Gaelic ceann a maigh meaning 'head of the plain'. This appears more plausible. Kemnay lies on the 300-foot contour, which encompasses Monymusk, Inverurie, Kintore and part of Skene.

At one time Kemnay belonged to one heritor, but at some time prior to 1688 the south eastern portion comprising the modern day farms of Lauchentilly and Scrapehard were purchased by Lord Kintore. These lands were subsequently sold to Lord Cowdray who annexed them to the estate of Castle Fraser, which he purchased around 1921. The area of land involved amounted to some 739 acres [Statistical Account of Scotland (1791 – 1799) Vol. XIV p.235].

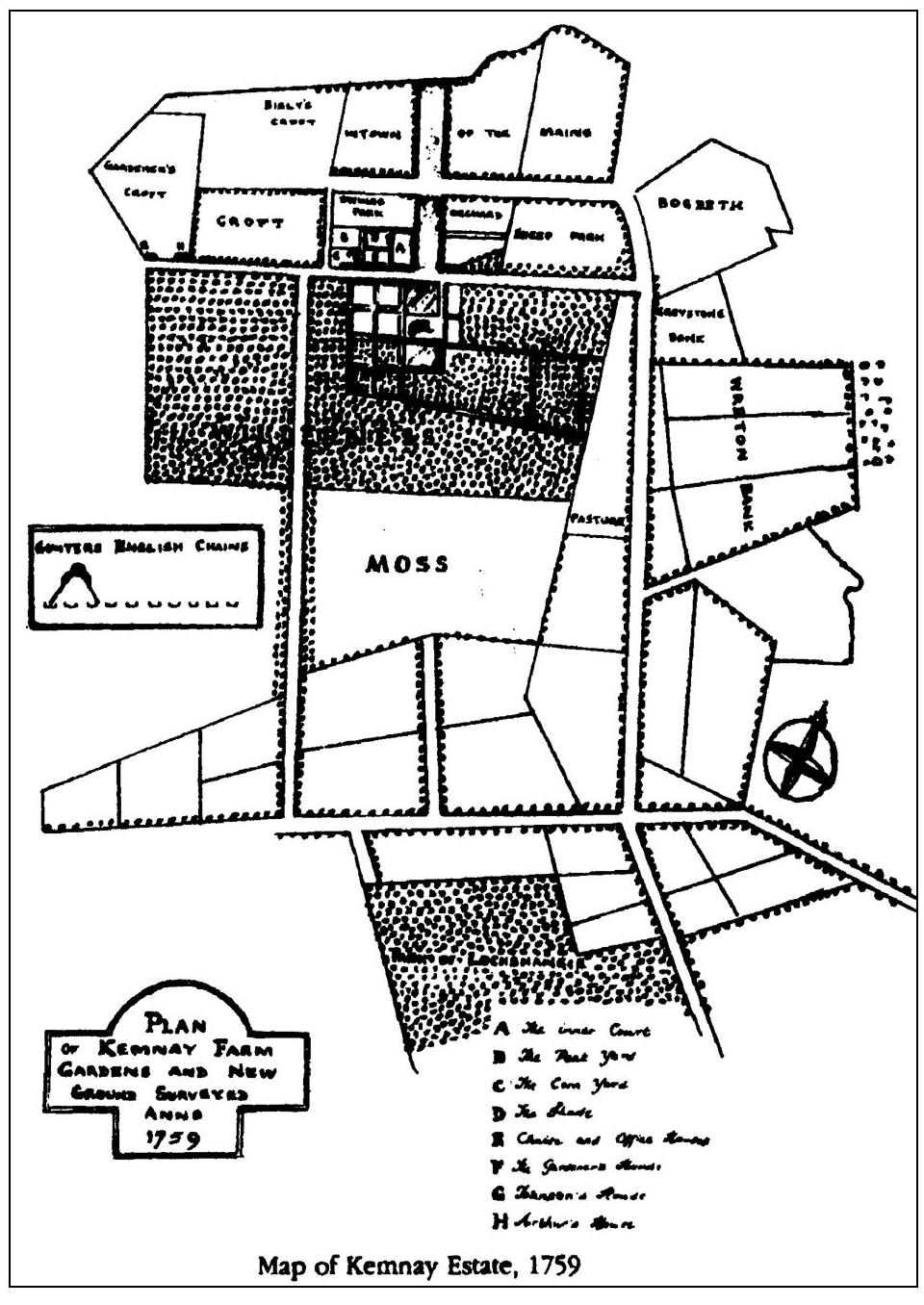

The remainder of Kemnay parish has belonged to the Burnett family since 1688. Several members of the family were involved as diplomats in Europe, but it was George (1714 - 1780) the third laird who was responsible for the early development of agriculture and arboriculture. An estate map of 1759 shows an area round Kemnay House covering some 130 acres which had at that time been enclosed with stone dykes and laid out in fields and part of it planted with trees.

IN THE BEGINNING

Since time immemorial man has taken from the ground that which Nature willingly provided. When Nature no longer supplied, man moved on to pastures new. Later, when man settled into small communities, he scratched the surface of the land and sowed what few seeds he had managed to keep from the previous season in the hopes that it would provide sufficient to keep him, his family and animals throughout the winter. This meagre existence was the lot of generations of folk, not only in the north east of Scotland, but throughout the country and even worldwide. When the crops failed, for whatever reason, be it inclement weather, early frosts or poor seed, the local folk had to depend on charity to see them through, not only a winter, but a summer too, until fresh grain from the following harvest would provide meal to fill their bellies, this being the staple diet in these far off times.

The closing years of the eighteenth century were particularly bad and the Kirk Session of Kemnay found it extremely difficult to satisfy the needs of the parishioners. At one point the Session purchased meal from outwith the area and distributed it among the poor. Human nature being as it is, ill feeling crept in among those who did not receive meal. Eventually the Session decided to supply the poor with money from the Poor's box and let the people obtain food where they could. [Kemnay Kirk Session Records (KKSR) Jan. and Jul. 1800, see appendix No. 2].

For many generations, land was divided out in small portions among the members of the community, so that any one member might have several parcels of land in the area. These could even be changed on an annual basis. The farming was purely subsistence; the people tried to grow sufficient to keep them and their animals throughout the winter and hopefully into the next spring when the countryside would green over and the cattle would once again get sufficient food to keep them going. Should the winter prove so hard that there was insufficient fodder, the cattle were killed off and the meat pickled. This practice was only changed when turnips began to be cultivated during the 18th century. The work was also carried out on a communal basis, each man maybe supplying an ox for the plough team. Therefore, all had to be in agreement before a specific task could be performed. This sometimes made the simplest of tasks a burden.

The land was divided into 'infield' and 'outfield'. The former was the land adjacent to the homestead and amounted to about one fifth of the holding. Any manure gathered over the year was spread on this area annually, and the land was cropped incessantly with bear (a type of barley) followed by two crops of oats then bear etc. The outfield lay further off and was generally of poorer quality. This was also divided into two unequal portions of about one third and two thirds. These were called folds and faughs. Grain, consisting of bear or oats, was grown as long as the ground would sustain a crop. It was then left to nature's devices and after some years it would green over with whatever weeds or grasses might grow. The cattle were pastured on this area and eventually it was ploughed and cropped again. Grain yields were low and it was considered good to reap four times that which had been sown; quite often it was much less [Anderson James LLD. 1794, General View of the agriculture and rural economy of the County of Aberdeen, p.54].

The abstract of the estate map of 1792 gives the division of land as follows:

| Acres | roods | falls | |||||

| Infield | 500 | 1 | 26 | ||||

| Outfield | viz folds | 339 | 6 | ||||

| faughs | 216 | 3 | 26 | ||||

| wetlands | 273 | 3 | 14 | ||||

| sum of outfields | 829 | 2 | 26 | ||||

| total arable | 1370 | 12 | |||||

| pasture | 253 | 12 | |||||

| woods etc | 160 | 3 | 36 | ||||

| moss | 212 | 3 | 6 | ||||

| 626 | 3 | 14 | |||||

| moor | 1350 | 1 | 16 | ||||

| total | 3307 | 1 | 2 |

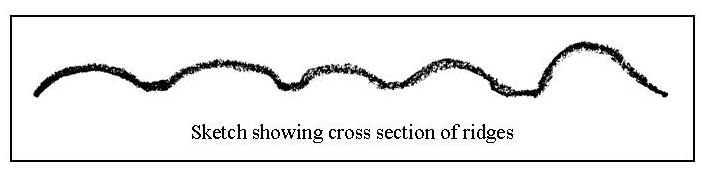

The land was ploughed into ridges and the crops were sown on these. These ridges were anything from twenty to thirty feet broad and anything from three to six feet in height [Scottish Historical Review, (1926 – 1927) Vol. 24 p. 195].

The land between the ridges acted as a kind of drain and also a receptacle for stones and rubbish gathered off the ridge. Implements were rather primitive and the communal plough, pulled by anything up to twelve oxen, was used to scratch the soil. These implements were cumbersome to use and with the large number of beasts involved, it took some distance to turn the plough round. Over the years the furrows or ridges took on a curved shape rather resembling the letter 'S'. Dr Anderson in his report of 1794 [p.77] said that 'the plough itself is beyond description bad.' and refused to give a description of it. He also considered it a waste of resources to keep so many oxen for one purpose only, that of ploughing, when horses were also kept as beasts of burden. His suggestion was that horses could be used both for ploughing and for carriage of goods. Many were of the opinion that the oxen produced dung for the fields and when they reached the end of their working life, they could be sold for meat, which was not the case with the horse.

By the time Kemnay Estate was surveyed in 1792, this annual practice of sharing land had ceased. Tenants held various portions which were still farmed in the old run rig system, [by this time leases of up to eleven years were being issued] and usually common grazings were shared amongst several of the tenants.

Racharral was divided between Alexander Mitchell who held 153 acres 3 roods 23 falls (this included 100a 29f of barren ground and moor) and 158a 1r 22f were shared by William Abel and Thomas Pirie (90a 1r 8f of this consisted of barren ground and moor). What is now the farm of Kirkstyle was divided between George Mitchell, 26a 1r 36f; Alexander Bisset, 21a 3r 9f; William Wallace, 8a 3r 23f; George Mackie, 6a 3r 11f and divided between them was 1a 1r 34f of pasture. The tenants had also a share of almost 200 acres of barren ground and moor, which lay to the south east of their land. This was common to the tenants of Parkhill, Hillhead, Kirkstyle and Written (Wreaton) [NRA(S) 1368, 1792 estate map].

Several areas were specifically laid out as crofts; Bogfur, Achoithie, Parkhill, Glenhead and part of Craigearn [NRA(S) 1368, 1792 estate map].

The parish of Kemnay is bounded on the north by the river Don and along its banks some of the alluvial soil was reasonably good. Elsewhere the soil was a light mould and very stony. There was a considerable amount of peat moss, which was used for fuel, not only by the people of Kemnay but also neighbouring parishes. Much of the parish at the end of the 18th century was rather barren. There was also what was described as burntland. This was part of the peat moss, which was ploughed in early summer and when the ground had dried sufficiently, it was set on fire. This gave reasonable crops for a year or two until all feeding disappeared from the soil [Statistical Account of Scotland (1791 – 1799) Vol. XIV p. 521].

Times, as they say, were a-changing. Development of agriculture in the south was being observed by Scottish landowners on their travels. Anxious to try out these new methods on their own lands, some of them hired men from England and from the Lothians to take over farms on their estates, with a view to improve these and with the hopes that their neighbours would do likewise [Alexander, William, (1888), The Making of Aberdeenshire, Transactions of the Aberdeen Philosophical Society, Vol. II p.114].

One of the early improvers was Elizabeth Mordaunt, daughter of the Earl of Peterborough, one of the great English improvers. She married the eldest son of the Duke of Gordon in 1706 and took with her men, implements and new ideas to her adopted home [Alexander William (1981) Northern Rural Life p.33].

These men from the south took with them their new ideas of enclosing fields by building dykes. This prevented the animals from roaming freely and allowed farmers to improve their stock by means of planned breeding, Crop rotation was introduced whereby different crops were grown which led to improvement in soil condition. The use of artificial grasses allowed for the making of hay which was used as winter feed for the animals, as well as turnips. These, along with potatoes became sustenance also for people. One of the common rotations was the five year; a white crop, oats or bear, was followed by a root crop, mainly turnips, then another white crop was under sown with grass which was cut for hay then grazed. A six year rotation was used in better quality soil which was able to sustain three years of grass.

Many of the improvements carried out consisted of clearing the land of stones and roots by trenching. In this method a trench some three feet wide and ten inches deep was cleared along one end of the field, or area to be improved, and the material removed elsewhere. The turf or divot from the next strip was laid face down in the bottom of the trench. Soil was then loosened by means of a tramp pick and all the stones and roots removed to the end of the field before placing the soil on top of the divots in the trench. The operation was steadily repeated along the remainder of the field. The stones, which were removed, were used in the construction of drains or in building dykes. Many of the stones encountered were too big to be moved by human effort. These were bored and split with gunpowder (Bennachie Again p.56). Sometimes there were more stones than were normally required to build dykes round the fields; in these cases larger dykes were built called 'consumption dykes' simply to use up the stones. There are several of these in the area of Aberdeen, notably at Kingswells where there is a large dyke some 500 yards long, thirty feet wide and six feet high with a footpath along the middle of the top [Hamilton, Henry (1945) Selections from the Monymusk Papers (1713 – 1715) p. lxvii].

Several methods of draining were carried out. Cross drains were put in about three feet deep with the main drains a little deeper. One type of drain consisted of a line of stones along each side of the trench and a flat stone laid on top bridging these two. Another type was to lay several lines of stones like inverted V's across the trench (/\/\/\/\/\). In both cases the drain was then filled up with stones to around a foot from the surface. If there were plenty divots, the stones were then covered with the divot grass down, preventing soil from penetrating the drain. This was a costly method, but in the end it reaped dividends.

Use of fertilisers such as lime and guano improved crop yields, but cartage expenses often made these uneconomic. The construction of the Aberdeenshire Canal allowed the carriage of fertilisers and other goods to Port Elphinstone at a more reasonable cost, as well as providing an outlet for surplus produce. Later on, railways improved the distribution further inland. The canal opened up central Aberdeenshire to a much wider market. A small snapshot of these times may be found in 'Inverurie Supplement'. Dr Davidson writes of the canal (p.4):

The throng of business that became common in the prosperous days of the canal was familiarly illustrated by the morning consumption of eggs at the change house which arose at Port Elphinstone, in a season suitable for carting from a distance. Eating two eggs a piece the number of farm servants congregated in the morning after journeys of from six to twenty miles despatched on Friday, the chief day, sometimes 80 dozens. That represented the number of carts laden with sacks of grain they had brought to the 'Port'. On such occasions, the landlady needed the whole hours of the night for baking oatcakes in readiness.

Lord Cullen purchased the neighbouring estate of Monymusk in 1712, and on his son Archibald's wedding in 1717 the estate was made over to him [Hamilton, Henry (1945) Selections from the Monymusk Papers (1713 – 1715) p. xliv]. Sir Archibald writing at that time says:

'All the farms were ill-disposed and mixed, different persons having alternated ridges; not one wheeled carriage on the estate, nor, indeed, any one road that would allow it.' He adds: 'In 1720 I could not, in chariote, get my wife from Aberdeen to Monymusk.' [Alexander, William, (1888), The Making of Aberdeenshire, Transactions of the Aberdeen Philosophical Society, Vol. II p. 107]

Sir Archibald practised as an advocate in Edinburgh and was from 1722 to 1732 a Member of Parliament at Westminster. This, however, did not deter him from initiating improvements on his estate. Much correspondence has been handed down on the improvements carried out at Monymusk and this gives a clear indication of the speed at which the work was carried out. Grant appointed Alexander Jaffray of Kingswells near Aberdeen to oversee the work. Jaffray was married to Christian Barclay, a member of one of the progressive families in the Mearns. Within three years considerable work had been carried out at the Home Farm; building dykes, making ditches, planting trees and introducing crops such as pease, clover and grass. Similar improvement work was carried out at the Moor of Tambeg.

It was not only on the farming side that things were changing. Grant implemented a programme of tree planting, both hardwoods and softwoods, in various places throughout the estate, round the mansion house and also at Pitfichie and Paradise. Nurseries were started and soon areas of land were enclosed with stone dykes and planted with trees. The quality of tree grown at Monymusk was eventually to set the standard for timber throughout the whole area [KKSR Feb 10 1780 See Appendix No.2].

Although much work was done at Monymusk during these early years, it was many years before the improvement works were completed. A plan of Upper Coullie dated 1798 [Monymusk Papers p. 148] has the heading:

'This map was prepared in connection with plans for the abolition of run rig and the creation of consolidated holdings.'

On the neighbouring estate of Kemnay, George Burnett had enclosed an area of some 130 acres around the house with dykes and some of it was planted with trees by the late 1750s. The area immediately round the House was laid out as a pleasure garden with walks and various species of tree, both hardwood and softwood. This wooded area was known as the Wilderness. On a map dated 1759, trees are shown planted round most of the field boundaries. This was one of the ideas imported from the south and the trees were more for decoration than shelter.

By 1792, when the whole estate was surveyed, these fields at the Home Farm had individual names and land which was pasture in 1759 was planted with 'larrix (larch) and birch'. The names include: High, Meikle, Mid, Little, Nether West; High, Low North; Upper, Nether Birkie; Little, Square, Meikle Kirtle; Meikle, Little Weaver; Little, Meikle Arthur, Wretton Bank; Greystone Bank; Bogbeth. Many of these names have disappeared over the years but some are still recognisable today. Bogbeth is now the recreation ground; the Greystone Bank contains a large glacial deposited rock mistakenly known as the Deil's Stane. There is another glacial deposit stone in the wood at the top of the field which was known as the Devil's Cradle.

The rest of the estate in 1792 is depicted with the run rig system still in evidence and large tracts of land as moor and moss. Each portion of land has the tenant's name written on it and it is obvious that any one tenant occupied different parts of land throughout the area.

Few changes took place on the agricultural front for almost half a century after George Burnett's early works, but there was considerable development on the forestry side. By 1792 there was a fir wood planted on top of Parkhill; an area shown as pasture alongside the Greenkirtle road in 1759, was planted with larrix and birch; while the hill of Lochshangie was partly [NRA(S) 1368, 1792 estate map]:

'large plantation of grown firs called the new wood of Lochshangie' and 'Old wood of Lochshangie formerly a plantation of firs now planted with different sorts of hardwoods'.

The hill of Paradise is shown mainly as moor but carries the caption:

'Top of Paradise on which formerly a plantation of firs'

The fact that the map shows moor is at variance with the report in the statistical account (see p.1) but the quotation is that of the surveyor. The land on top of the hill could quite easily have been of good quality although not at that time cultivated, having some time in the recent past been cleared of trees.

Paradise was a term used in the 17th and 18th centuries for an area enclosed and planted with trees [Alexander William M., The Place Names of Aberdeenshire, Third Spalding Club, p. 347].

Although improvements outwith the Home Farm were slow in being implemented, George Burnett persevered with the new methods to considerable advantage. In 1767 a sow (stack) of hay 48 feet long 12 feet broad with 6 feet high side walls and 12 feet 9 inches to the crown was built. The haystack in 1777 was 72 feet long 12 feet broad and 9 feet high in the side wall, an increase in volume over the ten years of some 125%. This was a phenomenal increase and had it been reflected in the other crops, would have given the laird great satisfaction. This extra produce would have enabled a larger stock of cattle to be kept. The records state that in 1767; '14 cattle were fed'.

THE WINEHOUSE ERA

Alexander Winehouse came to Kemnay House as a gardener in the early 1780s and spent the rest of his long life in employment there. He died on 17 July 1825 at the age of 80 years, having been in the service of the Burnett family for forty-four years. His last wages (£2. 10s for six months) were paid to him on 25 June 1825. In NRA(S) 1368 Bundle 244 contains a number of letters from Alexander Winehouse to John Burnett between 1808 and 1815. These letters deal mainly with accounts and estate work. It soon becomes obvious that considerable revenue came from the sale of timber from the estate and that several areas within the estate had been planted and were now reaching maturity.

Winehouse, in a letter to the laird dated 3rd March 1809, suggested that the time was right to hold a sale of timber, as prices were better than the previous year. He also thought that the lots should be kept small. The sale of fir wood in the park of Lochshangie was to be advertised for 10th April, but no records have been found giving the result. However, accounts list the following;

March 20 1809, for wood sold in Wilderness and Walkend park; £118. 19. 5.

March 20 1809, for wood bills payable 20 Dec 1808; £385. 4. 0.

On Dec 26 1808, 20000 larrix plants were purchased from Archibald Glennie for £5 and £7. 5s was paid for 84 lbs Scotts fir seeds for the hill of Achoithy.

The estate rental collected on 13 December 1815 amounted to £414. 8. 9. When one considers this sum against the above sum of £504. 3. 0, collected for timber sales from a small part of the estate, it brings into perspective the income already being derived from the forestry side of the estate. Tree planting gave employment, albeit seasonal, to a number of people. Building dykes round these areas to be planted was another source of employment to local men.

17 Dec 1810. … I have called on William Ronnald to finish off his part of the dykes on the hill of Achoithie against Whitesunday first and I have engaged other two men to build the remainder of that dykes in the spring [NRA(S) 1368, Bundle 244].

Also in April of 1809 James Duguid, a timber merchant from Aberdeen, offered three shillings per solid foot for 3 larrix fir trees in the wilderness. This was as a trial as larch had not at that time come readily on the market and people were not well acquainted with it. Alexander Winehouse requested an early reply from John Burnett otherwise Duguid might not take the trees. In November 1810 Mr Peter Pattello, a wood merchant in Aberdeen, bought some 3 dozen Scotts fir trees in the wilderness (for which he paid) and also asked for a similar quantity from the New Wilderness which Winehouse did not sell as he had no permission to do so. James Duguid had also purchased about 50 Scotts firr trees in the Walkend Park at 14d per foot and a large quantity of Scotts fir in the wood of Lochshangie. These were all to be cut down, measured and paid by Whitsunday.

Whether it was due to demand or to poor weather for harvesting, there was a scarcity of Scotts fir seed at that time; nonetheless this work of enclosing and planting went on for a number of years. Some 625 ells (the Scotch ell was 37.06") of dykes were built at Turchinach, 1265 ells of road were made on the hill of Achoithy at 1¼d per ell, 146 ells of road were made on the hill of Paradise at 3d per ell. During March and April 1812 some 75000 Scotts and Larrix fir plants were purchased and planted at a cost of £9. 19s.

During all this time of tree planting, it did not mean that the agricultural side of the estate was at a standstill. However, things were not developing as we would expect. The land which the laird had enclosed in the mid eighteenth century was let for cropping on a short term basis, and lime supplied by the laird had to be applied at the second crop and then laid down in grass. During the accounting period Dec 1814 to July 1815, £174. 17. 7 was received for the sale of timber. Expenditure, mainly on wages amounted to £48. 6. 9.

This shows the continuing dependence on income from forestry sales.

A letter from Winehouse to the laird dated 16th Nov 1808 contains the following:

… On Monday last the roup of the grass fields did very well, they brought a higher rent than could have been expected. There was 13 grass parks sett at the roup, beginning at the small parks on the south side of the moss road and came round by the four parks below the town of Lochshangie. The grass rent of these 13 parks for this last year's grass is £39. 10. sterl. The yearly rent for these same 13 parks obtained at the roup on Monday last amounts to £72. 13 sterl with 386 bolls of lime carried from Kintore and laid down contiguous to the fields next summer and after the separation of the crops from the grounds the lime is to be laid on the grounds and instantly the grounds is to be back furrowed by the purchasers. Along with the 2nd crop the heritor is to sow grass seeds and roll them down on his own expences in order to lay down the fields in grass crops again. The heritor also buys the lime and brings it to [from?] Kintore. The purchaser is to have 2 years crops of oats or bear.

Over the long period, which he worked at Kemnay Estate, Alexander Winehouse saw considerable changes. He arrived around the time of George Burnett's death and he served both Alexander and John. He was also a man of some position in the community, being admitted to the office of eldership in the parish kirk on September 2 1795; appointed session clerk on January 24 1802 following the resignation of the schoolmaster Charles Dawson; appointed treasurer on February 28 1808 after the death of Alexander Malcolm (KKSR See Appendix No. 2). He saw many thousands of trees planted and nurtured them over the years and no doubt witnessed several of them mature, felled and sold to the timber merchants.

In his time, too, quarrying operations started at Whitestones. Sale of stones from this quarry was also a further source of revenue and doubtless gave employment, although no record of this has been found [Kemnay Account Book 1823 – 1830]. Stone from this quarry was used in the construction of Waterloo Bridge, London as well as New London Bridge [McConnochie, Alexander Inkson, Donside, p. 60].

In 1820 and 1821 £103. 5s was received for 2065 tons of quarried stone.

Another source of revenue not generally recognised, was the sale of gravel. There was an old gravel pit at Parkhill marked on the 1792 map. During the nineteenth century and even into the twentieth century much gravel was excavated and sold from the area. This was mainly used in road making. Gravel was used to surface the estate drives annually.

THE MACALLAN YEARS

James MacAllan came to Kemnay House as a gardener early in 1823. It is assumed that he served his apprenticeship elsewhere. Born at Maidencraig near Aberdeen in 1799, he was not a robust man, being plagued with ill health for several years before his death in May 1841. He was appointed overseer following the death of Alexander Winehouse.

During MacAllan's term as overseer improvements such as ditching and trenching were carried out, and several requests for crofts were made. George Diack asked for a croft in 1823 and it was said:

'that he is worth two or three hundred pounds and is a very industrious man.'

Alexander Deans (1827) offered to build a new house if he were granted land for a croft. He was a wright and his family was to occupy Kirkstyle croft until 1923.

Benjamin Emslie (1827) was instrumental in the work of forming the burn at Dalmadilly. He was one of the first to come forward with an offer to pay for the work. It was felt pointless to ask those with land on top of the hill of Paradise to contribute as their land could be worked adequately without the need for drainage.

Whitestones farm came up for lease in 1827. At that time some 20 acres had been improved but much of it was considered very poor. It never was a very good farm although it was farmed by two generations of the Low family, who eventually vacated it around 1930.

In December 1837 William Rhonald had finished trenching ground near South Mains. This was a smallholding created out of some of the ground which George Burnett had enclosed in the 1750s. John Milne had finished making the road between the moss road and Greenkirtle. John Campbell had finished the ditch between Kirkstyle and Picktilam [sic], while Francis Ogg had nearly finished boring and blowing stones in the recently trenched ground at Kirkstyle and Rocharral. There were proposals to trench ground at Aquithie and Turshinach [sic]. All this is evidence that improvement work was being carried out in different areas of the estate.

It was reported in January 1838 that George Shand in Rocharral had improved some 6 acres since the previous harvest, and William Christie in Aquithie had been busy improving his barren ground. Benjamin Emslie was very busy dyking and improving and he was very anxious for work to commence on trenching a further area of land. It seems that the tenants were responsible for much of the land improvements, although the laird paid the wages of the labourers employed to do the work.

By April of that year another problem had raised its head. John Tindal, who had recently moved into the farm of Sunnyside had started ploughing up one year old grass to sow corn. He was most emphatic that he would not be tied to any specific rotational system, and would crop the farm as he pleased. Towards the end of the year he again proved difficult. It had been proposed to form a road to the farm of Sunnyside, but agreement could not be reached as to a route. He made considerable demands as to the ancillary works he wished carried out along with the making of the road and finally declared that if the work were not finished by the following February, he would make the road at the laird's expense.

MacAllan wrote to the laird regarding this whole episode:

'During the many years I have been in your service and the many people I have had to deal with I never met with any person so unreasonable and that I could make so little of.'

Things must have continued on a more even keel as John Tindal was still farming at Sunnyside in 1851[Census return 1851]. He died on 10 February 1860 and was buried in Bourtie Churchyard.

Towards the end of 1838 ditches were being dug beside ground trenched at Aquithie for John Watson as well as at Benjamin Emslie's and at Rocharral. These were to be sizeable watercourses whereas one to be cut between Duncan Cameron at Picktillam and Alexander Begg at Craigmile would not be so big. The most expensive item was to be trenching of ground for John Emslie at Wellbush. Wellbush was a farm created out of part of the land, which had been enclosed by George Burnett in the 1750s. It was also known as Greenkirtle. From this one would conclude that although it had been enclosed then, it possibly had not been cultivated to a very high standard. Doubtless this extra work of trenching on the farm meant an increase in rental which John Emslie found he was unable to pay as a warrant was taken out on 10 Nov 1851 to roup his effects in order to recoup arrears of rental.

The roup, which was held on 8th July 1852, offered for sale: 5 milk cows, 6 stots & queys, 2 work horses and riding poney [sic], carts, ploughs, a threshing machine, and a large assortment of farming utensils, household furniture etc., etc.

The above list is evidence that Emslie had certainly invested in his farm, which was in the region of 80 acres.

William Andrew, son of the blacksmith at Kirkstyle, then took over the farm. His son who retired in the early years of the 20th century, followed him in turn. This family is still represented in the village. The two Andrew brothers run a business making fireplaces [This firm closed in 2018]. The elder brother, George, stays at Wellbush.

A warrant was taken out against Peter Bruce in Milton in March 1852 and the roup advertised for 17th March offered for sale: 4 draught mares, a riding horse and colt, 7 milk cows, 13 stots & queys, 7 stacks of corn and fodder and a quantity of hay etc.

There is also a note of:

'Cautionary Obligation for rent due by John Mitchell late in Kirkstyle: 28 Aug 1854.' [NRA(S) 1368 Bundle 347].

Evidence that improvements were carried out to previously enclosed ground was again shown in June 1839 when William Findlay of South Mains (neighbouring holding to Wellbush) was burning the surface of ground which had been newly trenched. As a result of strong winds the fire jumped the ditch and everything being tinder dry, between one and two acres of young trees were burnt. The fire had almost reached the back wilderness when the wind mercifully dropped and that night the first rain for some time fell, quenching the fire.

A small snapshot of the area can be found in Chambers Edinburgh Journal, 16 January 1841. It is part of a longer article on the school at Kemnay and describes a journey from Inverurie to Kemnay:

Our way was for some time alongside the Don. We then left the river, and passed for some miles through a country generally barren, till at length we descended on Kemnay, which appeared to me quite as a green spot in the wilderness. I could imagine no simple rural scene possessed of greater beauty than what was presented by the little group of cottages constituting the parish school establishment, planted as they are upon somewhat irregular ground, which for some distance around has been laid out with good taste, and exhibits a variety of fine green shrubs.

During MacAllan's time as land steward, much of the estate was enclosed as we know it today and several of the tenants at that time were to farm in Kemnay for a long number of years. The Low family in Whitestones until around 1930, the Emslie family in the Mill and Aquithie until 1890s, the Malcolm family until 1980s and the Christie family in Aquithie until early 20th century.

THE DEVELOPING YEARS

In the evening of his days, John Burnett commissioned Alexander Ogg, a land surveyor, to survey the estate and put forward suggestions for development. In the previous few years Drainage Acts had been passed whereby Government loans became available to assist in improving the countryside by means of drainage.

Alexander Ogg built the house known as Howford just north of Inverurie on the Rothienorman road in 1844. He lived there for some time before moving to Aberdeen. He eventually emigrated [Rev. Dr. Davidson, Inverurie Supplement, (1886 – 1888), p.32).

The earliest of Ogg's reports is dated Aberdeen 2nd Feb 1847 and is entitled;

'Report by Alexander Ogg as to improvements on the estate of Kemnay. 1847'.

Having inspected this property generally with a view to its capabilities of improvement, I am of the opinion that a very large sum of money might be expended on it to very good account in draining entrenching and enclosing.'

He then goes on to suggest that the effects of draining and subsoiling on parts of the estate would reap great dividends over a short period of time. He was convinced that output could double in seven years. Areas, which he considered would be suitable for experimenting on, were at Roquharrold, Bogfur and Lochshangie. There was ample material for drainage, and he felt if good choice was made of the areas used for experiment, it might help to overcome the prejudices of the tenants. The report then goes on to say that considerable rearrangements of the boundaries of the farms would be necessary as some were so small that the tenants could not even survive although they did not pay rent. He recommended that:

'No farm should be less than sufficient to keep a pair of horses, no croft larger than to keep a cow or two excepting in the case of a carrier or carter or any one who has the means of making a living.'

The estimated cost of all the works outlined by Ogg was £5830 and he suggested that the laird should apply for a sum of £6000 and proceed with the work without delay.

Things appear to have moved quite speedily. By the beginning of June that year 27 acres had been drained at Lochshangie and 9 acres at Backhill at a cost of £60. 10.

Over the next year or so, Burnett invested heavily in developing the estate, spending almost £3000 [See Appendix 4]. No doubt this expenditure meant rent increases on the farms. Perhaps this precipitated the early removal of some of the tenants.

Ogg was very conscious of the attitude that some of the tenants had towards improvements. Many were content to scrape a living on land, which had given an existence to their forebears. Of the holdings on Lochshangie he said that:

The present boundaries or divisions of these possessions are very irregular and inconvenient and the proportion of land attached to each is such as to render the farming of them unprofitable to landlord and tenant.

Much of the farm of Lochshangie, then farmed by John Deans comprised part of the land which had been enclosed by George Burnett in the 1750s. It was proposed to straighten the boundaries thus increasing the holding from 90 acres to 105 acres. It was also suggested to erect new buildings to the east of the moss road and make this a model farm and to renovate the buildings at the top of the hill to give them a short life span. These proposed new buildings were never erected.

Ogg said that these additions:

'Would make the farm of such a size as to be laboured by a pair of horses and a pair of oxen.'

It was also suggested that the laird should find a tenant who:

'Ought to be a man possessed of capital energy and perseverance combined with a thorough knowledge of agriculture, as a great deal depends on this even after the proprietor has given all the encouragement he can reasonably be expected to do.'

Ogg also suggested that a lease of 22 years should be granted rather than the normal 19.

This is further evidence of the desire for new farming blood, which was needed in the area to try and throw off the old ideas that existed of 'what was good enough for my father should be good enough for me'. The longer lease would also give the tenant more encouragement to carry out improvements from which he might benefit through greater returns. The Durno family followed Deans in Lochshangie, and remained there until around the time of the First World War.

The holding of Alexr Forsyth's heirs, which comprised the land to the south of Lochshangie and between the crofts, and also the fields above the wood on top of the hill was proposed to be increased from 45 to 57 acres. Trenching and draining would be required and considerable additions and repairs to the buildings. These proposals he writes, would:

Make this a good pair horse farm.'

Forsyth's land was eventually absorbed into Durno's holding.

The three crofts were to have their boundaries adjusted, making minor differences in the acreages. These were at that time tenanted by: Robert Meston, William Clarihew and John Caithness. Mrs Cruickshank's holding was to be increased from 44 to 47 acres. This was the holding now known as West Leschangie.

The holdings listed under Lochshangie in the 1851 census are as follows:

Alexander Durno farmer of 70 acres

William Clarihew farmer of 30 acres

William Smith farmer of 50 acres

John Caithness farm servant

Alexander Morgan wood sawyer

Robert Meston master carpenter.

The above list shows that the forestry side of the estate was continuing to provide extra employment.

In the 1841 census there is no mention of the farm of Cairnton, but by 1851 Stuart M Burnett (younger brother of A G Burnett who was then laird) is farming 156 acres and employing 5 labourers.

Ogg reports on Cairnton (1847):

This farm notwithstanding its rough and uncultivated appearance I have formed a very high opinion of its capabilities and when the proposed turnpike is made it will be a very convenient farm. A considerable outlay, however, will be necessary both by proprietor and tenant in draining and trenching and also clearing the land of stones which last ought to be done by the tenant and the two former by the proprietor, the tenant agreeing to pay a percentage or so much additional rent.

It was proposed to lay the farm out in 5 fields. Clay from the ditches was to be spread on the moss in a dry spell. It was also suggested that Cairnton be used as a model farm to encourage others. A 22-year lease was recommended. A radical rearrangement of the crofts was suggested which it was feared would not please all the tenants, but it was felt that with the situation then existing some could not even survive though they were sitting rent free. Once again the proposed changes are not what are in existence at the present time.

The route of the proposed new turnpike was shown a little distance to the west of the road serving the Bogfur crofts, almost following the 400-foot contour. The route eventually chosen lay over the top of the hill, on the east side of the crofts.

Four crofts were proposed the acreages of which were to be 6.819 acres; 3.622 acres; 5.425 acres and 3 acres.

There is in the file containing Ogg's papers a report on Cairnton carried out in February 1863 by James Forbes Beattie. This report was prepared as the lease was due to expire at Whitsunday 1867 (suggesting that only a nineteen year lease had been granted initially) and gives conditions for vacation by the tenant, Stuart M Burnett.

The report lists all the improvements carried out during the course of the lease giving praise where due, but also criticising the poor standard to which most of the drains had been laid. A number of these had been inspected and found to be rather shallow laid, some only formed with branches of trees and most of them silted up. The stone dykes were also in poor condition.

Cairnton [the report states] is a secondary farm as regards soil. There is a good stocking of cattle upon it and it may be considered in fair condition but a great proportion of the land consists of a class of soil unfit in its present state of improvement for producing crops of the best or nourishing qualities.

By Mr Burnett's accounts it appears that for some years back he has been expending about £84 a year on extra manures. The expenditure on the buildings and thrashing machine amounted to:

| Dwelling house | 290. | 14. | 2 |

| Offices | 582. | 7. | 10 |

| Thrashing mill, mill dam, leads tail race etc | 86. | 13. | 0 |

| Cesspool or well | 1. | 1. | 0 |

| Dykes at 1849: £11. 17. 8 subsequently say £90 | 101. | 17. | 8 |

| Roads | 5. | . | 6 |

| 1067. | 14. | 2 |

This shows that considerable expenditure had been made during the lease. Cairnton was virtually a new holding, the lower part of which is shown as peat moss in the 1792 map. A large area of it is shown as moor. It says a lot for the endeavour of those involved that so much was taken into cultivation over a reasonably short period of time. The house and steading were built to a high standard as is evident today, but it appears that this desire for quality did not extend to the rest of the work carried out. The stone dykes must have been of a very inferior quality as in the short space of the lease they were in need of repair (a well built dyke should last almost a century [Callander, Robin (1982) Drystane Dyking in Deeside]. The standard of drainage left a lot to be desired. According to the report, the majority of the drains were silted up and in need of attention. Some had even been laid using only branches as the medium of drainage. It would appear that since that time new drains were laid as at present some of them are built culverts. It is obvious that supervision of improvement works on the farm must have been very poor. One would expect that the laird's brother would lead by example, but one must remember that the laird did not always do that, spending his time travelling on the continent and leaving the estate to run itself. His interest lay in getting income from it to fund his travels [Burnett, Susan, (1994) Without Fanfare, p.203].

According to the report, Mr Stuart Burnett wished to retire, or rather give up farming at Cairnton, as he was still only forty years old. The rest of the report considers different options open both to proprietor and tenant to facilitate this.

CONTINUING DEVELOPMENTS AS RECORDED IN CENSUS RECORDS

Of the 135 entries of dwellings in the 1841 census, 56 were farmers and 25 agricultural labourers. There were also 2 linen handloom weavers at Garpla Brae and one at Hillfold, 3 carpenters at Bogfur, 1 at Kirkstyle, 1 at Lochshangie and 1 at Scrapehard. This showed that the community was, to a large extent, still dependent on agriculture and the old practice of home weaving was still being carried out.

By the time of the 1851 census there were still 135 entries. Of these 51 were listed as farmers, albeit some only farmed 4 acres. There were 9 farm labourers, 9 general labourers, 2 dykers, 1 crofter/weaver, 5 sawyers, 1 carrier, 1 carter, 1 trencher and 16 tradesmen some of who also had crofts.

The change in occupation over the ten years is quite noticeable. The reliance on agriculture is lessening and there is an increase in qualified workers, many of them still agricultural related as in dyker and trencher, but nevertheless an improvement on being simply a day labourer.

By 1861 the quarries had been opened on Paradise hill by John Fyfe and a fair bit of development had taken place. There were 209 entries for the whole parish, 26 of which were quarry houses. There were 44 listed as farmers and 19 as crofters. There were 26 labourers of all kinds some of whom were also crofters, 1 dyker, 1 customer weaver, 6 sawyers, 1 wood merchant, 4 ploughmen, 1 carter, 1 forester, 1 gardener, 1 railway gauger, 1 railway labourer, 14 tradesmen. There were several quarry workers who also had holdings. This list of workers does not include servants staying with their masters, but only those in dwellings of their own.

The 1861 census reflects the coming of the railway and the quarries to the area. 'A Woodyard and Manufactory of Wood' is listed at the Mains of Kemnay and the 1866 ordnance survey map shows a saw and turning mill at Dalmadilly, showing that forestry was still giving considerable employment in the area. This is the first time that 'ploughman' as such has been mentioned. George Smith in Bogfur is listed as a 'crofter and millwright', an indication that the tradesmen were now willing to accept and participate in the manufacture of these new aids to the blossoming agriculture industry. In the space of some twenty years the parish of Kemnay had moved from an area totally dependent on agriculture for its existence to a parish which contained a number of good farms as well as other smaller and sometimes poorer units. There was also alternative employment at the now flourishing quarries.

Over the following forty years, this was to prove the life blood of the community, with quarries operating at various locations in the parish, although those at Paradise Hill were by far the most important. It was here that machinery was introduced which was to change the course of quarrying worldwide. It was found that by quarrying deeper, rather than horizontally into the face of the hill, a better quality stone was obtained. John Fyfe, along with others, developed machinery, which included the steam derrick crane and the blondin, an aerial cableway that facilitated the lifting of rock from the bottom of the pit and onto the rim of the quarry. It was at Kemnay too, that the first electronic detonation of rock took place, thereby making this part of the process more predictable and safer [Timepieces Publications, 1996, John Fyfe, One Hundred and Fifty Years 1846 – 1996]

ORDNANCE SURVEY MAPS

A study of the 1865 edition of the Ordnance Survey maps shows that by that time most of the land had been enclosed. There were considerable areas of peat moss around Turshoonock and Craigearn, part of which is shown as Monymusk Moss. An extensive area below the Lochshangie crofts is shown as Lauchintilly Moss. Near to this in the neighbouring parishes of Kintore and Skene are Bandshed Moss, Firley Moss and Skene Moss.

At one time the community depended on the peat for fuel, but by the time the map was prepared, many of these had been exhausted and were eventually drained and developed as farming land.

What soon becomes obvious is the density of woodlands in Monymusk parish, over Millstone Hill and around the east and north flanks of Bennachie. There are a number of plantations in Chapel of Garioch parish as well as farther south around Hill of Fare and Learney Hill. In Kemnay parish there are plantations on Lauchintilly, Lochshangie, Turshoonock, part of Parkhill, part of Aquithie and Roquharrold.

The wood on Parkhill was planted at the end of the eighteenth century and by the mid nineteenth a large part of it, there would be about five or six acres all told, had been cleared and the land was in cultivation. Doubtless this had been the work of David Webster who lived in the top croft at Parkhill and whose father's name first appeared in the account book in 1828 when he received payment for trenching at Cairnton and Bogfur. The Websters continued to live there until around 1907.

There are several plantations in Kintore, but as one moves eastwards through Fintray towards the coast, the incidence of agriculture increases and the incidence of woodland, other than shelter belts decreases. To the north of Bennachie the density of woodland again decreases.

The early work of Sir Archibald Grant did not go unnoticed amongst his neighbouring landowners. This central portion of Aberdeenshire appears as the most densely wooded area of the County.

CONCLUSION

On the admission of the Burnett family, Kemnay was always regarded as a reasonable size of estate for the second son of a second son. The inheritance due at that level would have been quite diluted. Financial wealth was never a strong point of the Kemnay Burnetts, and the early members of the family went out into Europe to earn a living as diplomats or legal men. Fortunes were never spawned in these circles and some members struggled hard to even get recognition by means of a pension.

George, the third Burnett laird, spent most of his time at Kemnay. It was he who was responsible for starting the improvement of the estate by enclosing several fields and planting an area with trees round his mansion house. He also planted trees extensively on Lochshangie Hill. Despite this early enthusiasm, the momentum of improvement waned. Within thirty years some of the pastureland was planted with trees (albeit it might have been rather poor pasture). Some seventy years after enclosing the land to the south east of the Big House, part of it was formed into holdings, viz. Greenkirtle and South Mains. Some of the fields were also let on a short-term basis.

The extensive planting of the middle and late 18th century eventually paid dividends. By the early years of the 19th century sales of timber from these plantations helped to pay the wage bills and fund further planting and land development. Neither was forestry the be all and end all. 'The fir wood of Parkhill' which was planted with larrix in 1810 was partly cultivated by the 1860s and eventually most of it came under cultivation.

Tree planting was carried out on a large scale in Aberdeenshire during the late eighteenth century. Sir Archibald Grant is credited with planting over 48 million on the estate of Monymusk. Between 1750 and 1806, Farquharson of Invercauld planted 16 million fir and 2 million larch trees around Braemar [Alexander, William (1981) Northern Rural Life p. 90]. Dr Anderson in his survey [p.31] wrote:

There is scarcely a gentleman possessing an estate of a hundred pounds a year who has not planted some hundred thousands of trees.

This extensive planting of trees transformed Aberdeenshire from a bleak and barren waste to a highly productive agricultural area. The trees provided shelter belts for the crops and also, in time, revenue for the landowners.

The successive Burnett lairds did not seem to be leaders in the improvement of the estate. They certainly were partners, funding some of the work that seemed to be initiated by the tenants. It was only when government loans became available in the late 1840s under the various Drainage Acts that any great effort was made to complete the enclosure and improvements on the estate. A. G. Burnett took full advantage of this money on offer and invested heavily, through grant aid, in the estate. Following this, several tenants, some of long standing, were removed due to rent arrears, further evidence that money was not altogether plentiful, and some farmers were still struggling to make a decent living.

By the mid 1860s most of the estate was under the plough. There were still areas left to develop such as Horner Howe and part of Glenhead. Horner Howe was laid out in crofts during the 1870s. The land was taken into cultivation by men who worked a twelve hour day at the recently opened quarries and who strove, in what spare time was available to them, to clear the boulders from their land and bring it into a state fit for crop growing.

Agricultural development is an ongoing process. Several of the reports in 1847 suggested amalgamation of holdings to make them more economic. This process has carried on over the years and is still with us at the end of the twentieth century. Although there is not much documented evidence of large-scale improvements in the early nineteenth century, improvements were no doubt being carried out. Ogg in one of his reports in 1847 stated:

… and as the plan of the property [1792 map] is now so completely changed unless on part of Lochshangie, the cheapest and most advisable plan will be to get a complete survey and plan of the whole estate.

One personal disappointment of the research project was the lack of specific documentation of improvements on the estate. I have lived in the shadow of the quarry hill all my life and expected to find information on the layout of the fields and the changes experienced by the developing quarries. At some point in time, part of one of the Kirkstyle fields was added to the quarry lands to accommodate an encroaching spoil heap. Whether documentation had ever existed is unknown.

It appears that the work was carried out on a large part by the tenants under their own initiative, with help, in the form of day labourers, being provided by the estate. In the relatively short period of research, much has been learned of the improvements carried out and one surprising aspect was that these were so late in being implemented, almost a century later than the original enclosures.

We of the late twentieth century are inclined to accept the dykes and fields of our surroundings as having been there for all time, whereas they have been in existence for barely a century and a half. It appears that many of them will not be with us for very much longer as the lumbering excavators move over some of the fields and consign them forever to oblivion.

It is somewhat sad that those who carried out the work of improvement by dint of human sweat and labour have mostly disappeared leaving little but their work as a memorial. Winehouse and MacAllan are commemorated in the churchyard, but many of the others go unrecorded. These include George Stevenson the joiner who had to ascertain the suitability of Monymusk timber, David Webster who struggled to clear the tree roots from the top of Parkhill to form a field in order to grow sufficient to support his family. The last of his line in the village died in 1958. Alexander Mitchell in Racharral moved to Chapel of Garioch in 1799. Descendants of his now live at Turriff and in Ontario in Canada.

This project started out to study the development of agriculture in the parish of Kemnay but the lack of sufficient estate records prevented the depth of research that was initially envisaged. One aspect that was previously not realised by the writer was the large amount of forestry planting that was carried out in Kemnay and the neighbouring estates during the period that was studied. The income from this planting was eventually used to finance development on the agriculture side as well as further forestry work.

Although I did not find in the archive what I originally expected, I have gained a wider knowledge of Kemnay Estate and its development over the years. This, together with work from earlier researches has allowed me to appreciate the problems faced by our forebears.

APPENDICES

Appendix 1

THE BURNETT LINEAGE AT KEMNAY

Thomas Burnet, 1st of Kemnay, was the second son of James Burnet of Craigmyle. He married Margaret Pearson, only child of John Pearson of Edinburgh. He purchased the estate of Kemnay in Aberdeenshire from Sir George Nicholson in 1688. He was a writer [lawyer] in Edinburgh and did not live long to enjoy his new purchase as he died in November 1688, some three months before the death of his wife in February 1689.

Their elder son Thomas (1656 - 1729) succeeded to the estate. He studied at the University of Leyden and was admitted to the Scottish Bar. After his succession to the estate Thomas employed a factor to run his affairs for him whilst he continued his 'peregrinations through most of the countries of Europe'. He spent time at the court of Sophia Electress of Hanover. On his way back to the continent in 1702, he was incarcerated for some 18 months in the Bastille and it was only through the good offices of the Electress that he gained his release. In 1713 he married Elizabeth daughter of Richard Brickenden of Inkpen, Berks, England.

Their son George (1714 - 1780) was to become the third Burnett laird of Kemnay. He was also the first provost of Inverurie. George became the first of the improving lairds of Kemnay and by 1759 he had some 130 acres to the south east of the Big House laid out with woodland and enclosed in fields. It was in his time that the avenue was planted and much of what became known as the wilderness was planted out as pleasure gardens with walks and many exotic trees. He was amongst the first of the improvers to grow turnips in the fields. He married Helen daughter of Sir Alexander Burnet of Leys in 1734.

Alexander Burnett (1735 - 1802), their son, was for several years Secretary to Sir Andrew Mitchell of Thainstone who was Minister to the Court of Berlin. Following Mitchell's death, he was Chargé d'Affaires for some two years. In all he spent sixteen years abroad. He returned home in 1772 and settled in Aberdeen. On the death of his father in 1780, he continued the work of development on the estate begun by him. In 1781 he married Christian, daughter of John Leslie, professor of Greek at Aberdeen and of Christian, daughter and heiress of Hugh Fraser of Powis. Their eldest son George, born in 1783, died the same year. Helen (1784 - 1864) married Dr James Bannerman, professor of Medicine in the University of Aberdeen in 1805. John (1786 - 1847) the 5th laird married Mary daughter of Dr Charles Stuart of Dunearn, Fife. There were a further three members of the family; Elizabeth born 1788, Christian born 1789 and Lamont born 1791.

Following Alexander's death in 1802 much of the management of the estate was carried on by his widow, Christian. She continued to live at Kemnay until John's marriage in 1814, although he had been running the estate since his return in 1810. John continued the improvements around the estate, and it was in his time that the house was extended and altered in the 1830s. The architect was John Smith, the first city architect of Aberdeen. His family were; Mary Erskine, (1815 - 1890), Alexander George, 6th laird of Kemnay (1816 - 1908), Christina Leslie (1818 - 1866), Charles John (1820 - 1907), Georg

Alexander George Burnett was a somewhat eccentric gent. It was in his time that much of the agricultural changes took place on the estate, but AG spent a lot of his time touring Europe, writing papers on his travels and preaching. He had a private chapel on the estate. He married Letitia Amelia, daughter of Wiliam Kendall in 1849 and by her had four of a family; Letitia (1850 - 1936), John Alexander 7th laird (1852 - 1935), William Kendall (1854 - 1912) who became a lawyer in Aberdeen and handled much of the estate work, Amelia (1855 - 1941) who married Dr James Stark, another somewhat eccentric preacher and author, a congregationalist. Letitia Amelia died in 1855 and AG married Anna Maria Pledge in 1877 by whom he had Ebenezer Erskine (1877 - 1951), Alexander Douglas Gilbert (1879 - 1962), Henry Martyn (1881 - 1915) Octavious Winslow b & d 1882, Stuart Alexander b & d 1883, Frances Mary Stuart (1884 - 1976). Anna Maria died in 1885 and AG married Emily Julia Burch in 1893. She died in 1908.

John A Burnett married Charlotte Susan, daughter of Arthur Forbes Gordon of Rayne in 1877. He was 56 when he succeeded to the estate. During the First World War he served in France with the French Ambulance Corps for which he was awarded the Croix de Guerre. Due, no doubt, to a great lack of foresight on the part of his father, he had received no formal training on estate management. He had studied medicine in his younger days and toured with the D'Oyly Carte Opera company as their medic. Having had no formal income, he had to borrow considerably to live. It was during his tenure in the 1920s that much of the estate was sold off. His family were; Arthur Moubray 8th laird (1872 - 1948), Lettie Muriel (1880 - 1966), Charles Stuart (1882 - 1945) Air Chief Marshal, Thomas Leslie (1885 - 1940), Robert Lindsay (1887 - 1959) Admiral Irene Dorothy May (1893 - 1982).

Arthur Moubray Burnett joined the Brocklebank Line in Liverpool as an apprentice in 1894 and sailed with that line between Liverpool and Calcutta for four years. He served in the Merchant Navy until 1906, leaving with the rank of 2nd Officer. He worked for the Continental Electric Company in India until the outbreak of war in 1914 when he joined the Calcutta Scottish. He served with them in East Africa later transferring to the Kings African Rifles. He was invalided out and sent to India in 1917. He married Muriel, widow of Seymour Langham, one of his old time friends, in 1921. His elder daughter Susan Letitia was born in October 1922 and his younger daughter Jean Muriel Moubray was born in 1926.

Susan Letitia served with the WRNS during the war. She met and married Fredrick J Milton who was serving with the South African Air Force. After the war they returned and farmed in South Africa. Her mother died in 1963 and in 1964 she returned to Kemnay.

Appendix 2

KEMNAY KIRK SESSION RECORDS

February 10 1780. The Session taking into consideration the ruinous state of the churchyard dyke and gate agreed to have the same repaired as soon as the weather permits and to send to William Elmslie to come and do the mason work and appointed George Stevenson to purchase wood for the gate, and for the pews which are also to be repaired, at Monymusk if it is to be found proper for the purpose.

Septr 2 1795. … Eod die Sess. Being met and constitute, distributed tokens. They then proceeded to consider of the election of Alexander Winehouse to be one of their number: and no objection having been made to his life and character by the congregation, he was instructed in his duty as an elder by the Modr. And admitted … receiving from the several members of the Session the right hand of Fellowship.

Jan 12 1800. … the Moderator called their (the Session) attention to the distresses of the poor in this season of scarcity and dearth, and mentioned to them the propriety of his recommending from the pulpit to the whole people of the Parish, to give, each, something extraordinary to the Box every Lord's day, that, if possible, a fund might be created, against Whitsunday, for reducing the price of meal to the most necessitous during the ensuing summer.

June 29 1800 … The Moderator then explained the object of their present meeting, which is to take under their consideration the means of alleviating the distress in this Parish arising from the high price and scarcity of meal. He represented that, having along with James Davidson, servant to Mr Burnett of Kemnay, gone thro the whole parish, and endeavoured to ascertain what quantity of meal it would be necessary to bring into it betwixt this time and harvest. It was found that about seventy bolls would be wanted, above what the Parish can furnish of its own produce. The Modr. further stated, that he had drawn up a list of persons, including the Parish poor, who are unable to buy meal at the present exorbitant price of 2/- per peck of Bear meal and 2/6 per peck of oat meal … that on this list, there are 46 persons, who will need at least 40 bolls of meal, which the Modr. proposes to the Session to reduce /6 per peck, which will require £16 Stg. He also informed the Session that he had bought 26 Bolls of oatmeal, which cost £48. 16. that is 2/4½ pr peck; that he has paid the price of this meal, and brought part of it already into the Parish at his own expense … and that he intends to do what he can to procure more. And in order to raise the £16 above mentioned, he proposed to the Session to anticipate their ordinary income to the amount of £5, which he offered to advance untill Martinmas next, and to devote to the same purpose £5 of the savings at present in their hands, which have arisen from the extraordinary weekly collections that have been made in the Church during this season. … Session unanimously agreed to adopt the above plan; and undertook to indemnify the Modr. from any loss that may arise from deficiency of weight in selling out the meal in small quantities.

July 31 1800. … And the Session, upon mature deliberation, considering that their exertions for supplying the necessitous of the parish, have given rise to much heartburning and envy on the part of many of the parishioners whom the Session could not consider as objects of charity, and to uncandid reflections on the Session themselves. They were unanimously of the opinion that it will be most conducive to the interests of religion and humanity, to divide among the poor the money now in their hands, and let them procure meal for themselves wherever it can be got.

Jany 24 1802. … Session was called, and being met and constitute, Sedt. The Modr. And Alexander Winehouse, Al Smith and Charles Sang, Elders. The Sessionm, considering that Chas Dawson resigned his office of Clerk on the 30th December last, and had not since that time, manifested any desire to resume it again, proceeded to elect another clerk, when Alexander Winehouse, one of the Elders was unanimously chosen.

At Kemnay the 28 Feby 1808 years. The which day the Session being met and constitute by prayer. … At this Sederunt, Alexr Winehouse, one of the Elders, was unanimously chosen Kirk Treasurer, in the room of Alexr Malcolm deceased.

Appendix 3

BURNETT ARCHIVE BUNDLE 244

Kemnay 16th Nov 1808. … On Monday last the roup of the grass fields did very well, they brought a higher rent than could have been expected, there was 13 grass parks sett at the roup, beginning at the small parks on the south side of the moss road and came round by the four parks below the town of Lochshangie. The grass rent of these 13 parks for this last years grass is £39. 10: sterl. The yearly rent for these same 13 parks obtained at the Roup on Monday last amounts to £72. 13: sterl. with [?] 386 bolls of lime carried from Kintore and laid down contiguous to the fields next summer and after the seperation [sic] of the crops from the grounds the lime is to be laid on the grounds and instantly the grounds is to be back furrowed by the purchasers. Along with the 2nd crop the heritor is to sow grass seeds and roll them down on his own expences, in order to lay down the fields in grass crops again. The heritor also buys the lime and brings it to Kintore. The purchasers is to have 2 years crops of the fields of oats or bear.

Appendix 4

BURNETT ARCHIVE BUNDLE 328

Monies expended by A G Burnett prior to 14 Aug 1848

| On Cairnton and Bogfur: | inc. trenching | £101. 5. 9 | |

| Backhill | inc. trenching | 44. 3. 3 | |

| Craigearn | |||

| Dalmadilly | |||

| Lochshangie | inc. trenching | 26. 9. 10 | |

| Wood supplied from plantations | |||

| Expenses prior to 14 Aug 1848 | trenching included | 636. 17. 4 | |

| deduct trenching | 171. 18. 10 | ||

| £ 464. 18. 6 |

| Cairnton & Bogfur | £ 899. 14. 10 |

| Backhill | 88. 10. 5 |

| Craigearn | 70. 11. 1 |

| Glenhead | 6. 7. 6 |

| Aquhythie | 6. 12. 3 |

| Lochshangie | 149. 7. 7 |

| Mains of Kemnay | 30. 0. 0 |

| Mansion House, Ground Officers | |

| House and Home Farm Offices | 187. 2. 2 |

| Milltown | 526. 12. 6 |

| Easter Roquharrold | 526. 12. 6 |

| Whitestones | 5. 0. 0 |

| Wood supplied from plantations | 152. 8. 10 |

| Expenses inc. trenching | 2265. 19. 4 |

| Trenching | 198. 11. 2 |

| Expenses, trenching exc. | 2067. 2. 2 |

Appendix 5

CONCISE SCOTS DICTIONARY.

1. For wheat, peas, beans, meal, etc.

| 1 lippie (or forpet) | 2.268 litres | |

| 4 lippies | = 1 peck | 9.072 litres |

| 4 pecks | = 1 firlot | 36.286 litres |

| 4 firlots | = 1 boll | 145.145 litres |

| 16 boll | = 1 chalder | 2322.324 litres |

2. For barley, oats, malt.

| 1 lippie (or forpet) | 3.037 litres | |

| 4 lippies | = 1 peck | 13.229 litres |

| 4 pecks | = 1 firlot | 52.916 litres |

| 4 firlots | = 1 boll | 211.664 litres |

| 16 boll | = 1 chalder | 3386.624 litres |

Linear and square measures

According to the standard ELL of Edinburgh.

Linear

| 1 Scots foot | = 12.0192 inches (Imp) | 30.5287 centimetres |

| 31/12 feet | = 1 ell | 94.1318 centimetres |

| 6 ells | = 1 fall | 5.6479 metres |

| 4 falls | = 1 chain | 22.5916 metres |

| 10 chains | = 1 furlong | 225.916 metres |

| 8 furlongs | = 1 mile 1976.522 yards | 1.8073 kilometres |

Square

| Scots | imperial | metric | |

| 1 sq inch | 1.0256 sqinch | 6.4516 sq centimetres | |

| 1 sq ell | 1.059 sq yards | .8853 sq metre | |

| 36 sq ells | = 1 sq fall | 38.125 sq yards | 31.87 sq metres |

| 40 falls | = 1 sq rood | 1525 sq yards | 12.7483 ares |

| 4 roods | = 1 sq acre | 6100 sq yards (1.26 acres) | .5099 hectare |

BIBLIOGRAPHY LIST

ALEXANDER, William M (1952). The Place Names of Aberdeenshire. Third Spalding Club, Aberdeen.

ALEXANDER, William, (1981) republished. Northern Rural Life. Robin Callander.

ALEXANDER, William, LLD. (1888). The Making of Aberdeenshire. Transactions of the Aberdeen Philosophical Society, Vol II. Aberdeen 1892.

ANDERSON JAMES LLD. (1794). General view of the agriculture and rural economy of the County of Aberdeen. Edinburgh

BURNETT FAMILY ARCHIVES, Kemnay House.

BURNETT, Susan. (1994). Without Fanfare. Kemnay House Publishing.

CENSUS RETURNS. 1841, 1851, 1861.

DOWNIE, D A; MORRISON D M; MUIRHEAD A M (1995). Tales o' the maisters. Time Pieces Publications.

FENTON ALEXANDER, (1987). Country Life in Scotland, our rural past. John Donald Publishers Ltd, Edinburgh.

HAMILTON, Henry D. Litt.. Editor. (1945). Selections from the Monymusk Papers (1713-1715). Scottish History Society.

INVERURIE SUPPLEMENT. Rev Dr Davidson (1886-1888). This is in fact copies of the kirk magazine of Inverurie Parish Kirk. It consists of a single sheet of paper published monthly and giving church notices. Dr Davidson also has a feature 'Recollections of forty years', in which he notes some of the happenings in the area over the time of his long ministry. A bound copy is held in the Bailies of Bennachie Library at The Bennachie Centre.

JOHN FYFE, ONE HUNDRED AND FIFTY YEARS 1846 - 1996. This is a small booklet published by Time Pieces Publications to mark the above anniversary of John Fyfe in business.

JOHNSTON, James B. BD. FRHistS. (1970) Place-names of Scotland. SR Publishers Ltd. (Republished).

KEITH, George Skene DD (1811). A general view of the agriculture of Aberdeenshire. D Chalmers & Co Aberdeen.

MACKIE, Alexander (1915). Aberdeenshire. Cambridge University Press.

MCCONNOCHIE, ALEX INKSON, (nd). Donside. W Jolly & Sons, Aberdeen.

ORDNANCE SURVEY MAPS. 1867 edition. Scale six inches to one mile.

PEARSON, Mowbray, Editor (1994). More frost and snow, The diary of Janet Burnet 1758- 1795. Canongate Academic.

SCOTS DICTIONARY, CONCISE. (1985). Aberdeen University Press.

SCOTTISH HISTORICAL REVIEW. (1926 - 27). vol 24. Ridge cultivation in Scotland, Arthur Birnie.

SHAPIRO, Hyman (1968). Scotland in the days of Burns. Longman Group Ltd.

SMITH, Alexander (1875). A new history of Aberdeenshire; 2 volumes. Lewis Smith, Aberdeen.

SMOUT, T C. (1969). A history of the Scottish people 1560- 1830. Collins, London.

STATISTICAL ACCOUNT OF SCOTLAND (1843). Aberdeenshire.

STATISTICAL ACCOUNT OF SCOTLAND 1791- 1799. Edited by Sir John Sinclair, (1982). Vol. XV. North and East Aberdeenshire. EP Publishing Ltd.

STATISTICAL ACCOUNT OF SCOTLAND 1791-1799. Edited by Sir John Sinclair, (1982). Vol. XIV. Kincardineshire and South and West Aberdeenshire. EP Publishing Ltd.

STATISTICAL ACCOUNT OF SCOTLAND, THIRD. (1960). The County of Aberdeen. Collins, Glasgow.

WHITELEY, Archie W M Editor. (1983). Bennachie Again. Bailies of Bennachie.