Being the oldest timber merchant in these parts, I have been asked to collect a few memories of lumbering upon Deeside, and to set them down in writing. It is well to understand that I claim no experience whatsoever in composition beyond the dictating of very brief business missives.

This is now my fiftieth year in the wood trade, for it was in 1875 that I was blown off the land and out of farm service in the Garioch, to contract for felling and hauling at Tillyfourie on Donside.

Gales have a very considerable influence over the home timber trade. Trees that are laid low by a storm deteriorate rapidly, and the landed proprietors must proceed to dispose of them as quickly as possible. Under such circumstances the market is heavily supplied, and trade fluctuates.

The first gale that I remember definitely was in October in one of the early ‘sixties. I had just gone back for another winter at Blairdaff School, when the fine fir wood lying between Manar House and Auchorthies Roman Catholic College was as completely levelled as if a heavy roller had passed over it. This particular area is now mostly covered with scrub.

At Tillyfourie, in our first wooden bothy in the woods, my attention was repeatedly distracted from my early morning culinary duties (just porridge) by a tap-tapping upon our happy home. Morning after morning I failed to find out what it could be until, looking up into the tall larches, I espied half-a-dozen squirrels busy pulling off cones, picking out the seeds, and dropping the husks on the bothy roof.

In the winter of 1876-1877 we moved further up the Don to a spot close to the river on the south side, a mile or two below Mossat. There, in a hut with my brother, I experienced the heaviest snowstorm I have known. That was the time when Captain Nares claimed to have gone furthest North towards the Pole. It snowed, out of the east, for a solid week continuously, and our food ran short. My brother set off on horseback to the shop at Bridgend, where a man had arrived before him from Lumsden on foot with a bag of loaves: but so many woodmen and farm-servants were waiting that my brother got nothing. That winter about 150 men were working in the woods thereabouts. The merchant hunted through his store, and fortunately came upon a box of old broken farthing biscuits, which he emptied into a horse’s feeding bag. My brother secured these, and for a week we had nothing to eat but farthing biscuits and one salmon. For water we had to break the ice on the Don. One night, whilst fetching water by the light of a lantern, I saw a salmon, and, going back for our stable graip, managed to spear him. By good luck we had plenty of hay for the horses. When the fall ceased, all the woodmen turned out to cut the drifts for the snow plough to allow the carriers up from Alford. In those days men did not stop to ask who would pay, or how much. That was the nearest approach to starvation in my whole experience.

In 1880 I moved, in early spring, nearer to Deeside, to the hill of Carnie, Skene, having contracted to cart wood for Messrs. Paterson. From then till now, a period of 44 years, I have never ceased to have regular business relations with this firm, which is now celebrating its centenary in the wood trade. At Skene, on this occasion, it was the gale of the last days of 1879-the gale that swept away the Tay Bridge-which brought me a contract. I undertook to cart all the blown timber on Carnie of Skene to Paterson’s mill near Echt. This job lasted about nine months.

In December, 1881, it was discovered that the body of the Earl 0f Balcarres, Laird of Dunecht, was missing from the mausoleum under the Chapel floor, where it had been placed some months before. The lead coffin had been cut like the back of an envelope, diagonally both ways, and the sections folded back. What a hue and cry in the country side! The body was found about seven months after in a shallow ditch, covered with leaves and branches. The abstractor (or abstractors) had expected that a reward would be offered, which they might be able to claim. One Souter, a rat-catcher, was imprisoned. Well do I remember how all and sundry, police and civilians, joined in the search and came poking among the sawdust at our mill.

The opening weeks of 1881 found us at Blackhall, on the south side of the Dee, above Banchory, and this time dragging timber for Paterson from the high land west of Scolty and Blackhall to the river bank opposite Cairnton, whence the logs were floated down the Dee to Paterson’s mil1 at Silverbank, a mile or so below Banchory.

Our drag roads to the river bank were exceedingly rough. This part of Deeside is covered with huge boulders deposited by the receding ice of a past age. Every day one, at least, of our horses would tear off a shoe, and the nearest smithy was at Braehead, Bridge of Feugh. We had soon to learn to put on shoes ourselves. I had two brothers with me at this job, which lasted about eight months, and it was the winter during which the New Market was burned down in Aberdeen. So rough is this woodland with boulders and water holes, that both contractors who have been felling in this district in recent years have constructed light railways for transport purposes. A Ford tractor on iron wheels has proved a good and efficient locomotive. But in our time there we had a day of ten hours, and were glad if we could complete six drags of one-half or three-quarters of a mile to the river bank. The trees from the top of the hill were very large, and one heavy cut of a tree made a good load. Horse and man set off down hill, and frequently a tree, slipping down too quickly, would push horse and man some distance before it. My brother Charlie had an exciting experience one day. The path, as it approached the river, skirted the edge of the high and precipitous bank. Charlie’s little stallion was dragging one big tree, narrow end foremost, along this path, when suddenly the heavy end jolted over the edge. The horse, feeling the extra weight, realised the danger of being pulled backwards over the cliff, and stood his ground well. The tree, dangling over the edge, unrolled itself from the chain, struck a ledge with its heavy end, and was tossed like a caber into mid-stream, to the great consternation of a salmon fisher from Cairnton Lodge, who got very thoroughly soaked and was never seen fishing there again. Our job was finished when we delivered the trees at the river bank to the floating contractor. I believe that these were the last trees to be formed into rafts and systematically floated down the Dee. I never heard of floating after that.

I will try to make a representation of a raft. There was never much loose logging in Scotland. That is an American system of floating, which would have destroyed our bridges had the logs got piled up against the piers. The trees were laid in the water in two rows, thick end to thick end. Iron dogs with a ring were driven into the thick end of each tree, and the thick ends of the trees were laced up against each other with a rope passed through the rings in the dogs in each tree alternately. The thin ends of the trees at stem and stern of the raft were bound together with a rope and a thin lacing tree for a cross spar. With three men aboard using guiding ropes, and poles in shallow water I the raft was floated down. The men on board always got very wet. Their work was most arduous and highly dangerous, and floaters were invariably hard drinkers. The chief floater was a contract worker, and he provided his own dogs, ropes, poles, etc., for his squad. The chief floater on this last occasion became afterwards forester at Dess. The short passage of his rafts was over the most dangerous part of the Dee, namely, the Glisters, opposite Invercannie Waterworks outlet, on Blackhall water. At the Glisters it is evident that the rocks in the bed of the river have been blasted at some time to make a better passage for rafts. At Blackhall I noticed that the Dee rose and fell in good weather without rain, when it was said that the wind was blowing additional water out of the lochs up country. The late Rev. John Grant Michie, of Dinnet, mentioned in his “Autobiography “ (see his “Deeside Tales,” ed. 1908, p. 206, et seq.) that about 1820 a dam had been constructed in Glen Derry to store water to float timber down the Dee, and that it was constructed by none other than the famous gentleman poacher, Sandy Davidson (obiit 1843), who had purchased timber from the Earl of Fife to bring it to market in Aberdeen. Certain it is that timber was floated right down to Aberdeen in the early years of the nineteenth century

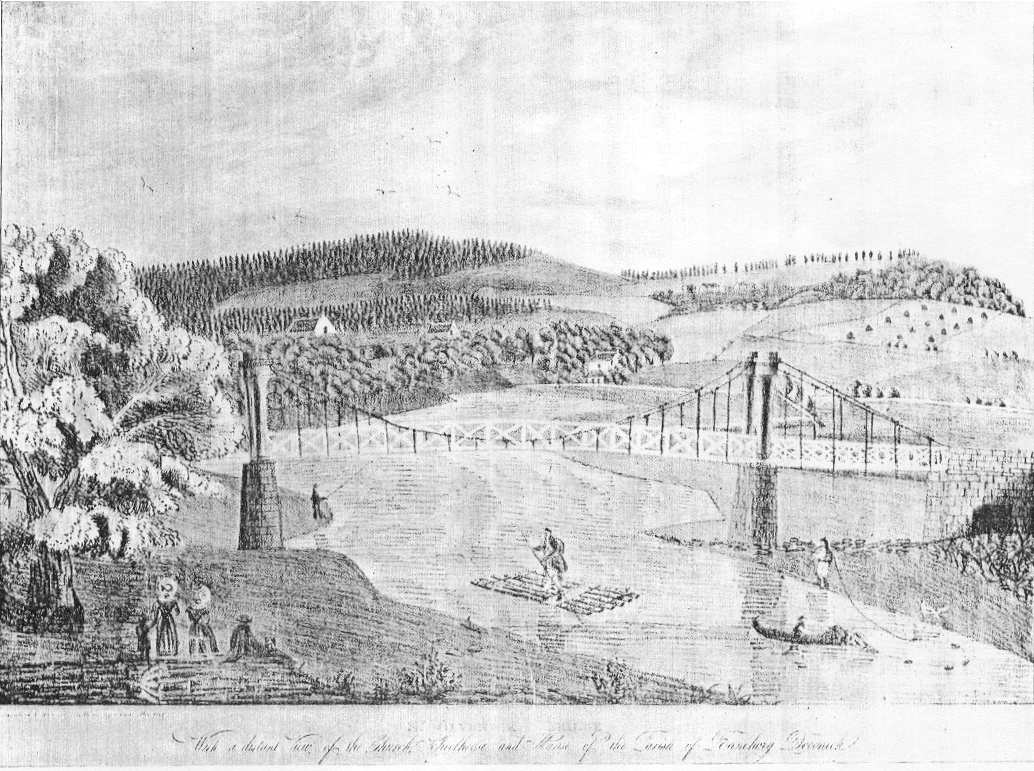

ST. DEVENICK'S BRIDGE

From a lithograph (executed probably 80 or more years ago) by Eliza Mearns, a niece of Dr George Morison who erected the Bridge at his own expense in 1837.

There were several houses of call on the banks of the Dee which the floaters used to visit for food, and especially for drink. The dangers of floating, its hardships and difficulties need not be emphasized, nor the generally rough type of men who followed this occupation. One of these river inns was kept towards the time of the opening of the Deeside railway (to Banchory, 7th September, 1853) by Meggie Davidson, sister of the afore-mentioned gentleman poacher, Alex- ander Davidson. Such “ boozin’ and playin’ o’ cairts “ and prick the garter as these boys indulged in have not been heard of since their time. The house was at the top of the bank opposite Dalmaik farm at the ford from Drumoak to Durris. When the trains came up the valley with a new method of transport, Meggie had to adopt another occupation, and went about the district with a pair of baskets on her arms collecting eggs. It is of interest to note that John Blake Macdonald, a noted Scottish painter, was a floater on the Dee at one time. He was the son of James Macdonald, a Speyside timber merchant, and was born at Boharm, Morayshire. on 24th May, 1829, and, after a parish schooling, he worked for some years as a floater on the Spey, which was used as a floating agent far more than the Dee. He was floating on the Dee about Banchory in the early ‘fifties, and had already attained such skill in portrait painting that many farmers of the better class and well-to-do people employed him. Several of his portraits of them are still about Lower Deeside, for example, in the Bank House, Station Road, Banchory, and in Maybank, Crathes. By the advice of these patrons he entered the Academy of the Board of Trustees, Edinburgh, and in 1862 won the first prize for painting from life at the Royal Scottish Academy (“Associate,” 1862; “Academician,” 1877). His most important pictures dealt with dramatic or picturesque episodes in Highland history or Jacobite romance. “Prince Charlie leaving Scotland” and “Glencoe, 1692,’. are two of his best things.

I might have chosen as my text, “ It’s an ill win’ that blaws naebody guid,” for that same gale of late 1879 gave me four years’ further contract work for Paterson’s at Braemar, to deliver at the mill all the blown timber on the estate of Invercauld. I remember bringing in the biggest larch that I have ever seen. It must have been about 150 years old, and was one of the first larches to be planted in Scotland. It was away back in the middle of the eighteenth century, when the Duke of Atholl, in Perthshire, and the Farquharsons, on Deeside, and Sir Archibald Grant, of Monymusk, on Donside, introduced the larch, which is a native of Russia. To-day in Scotland the larch is the most valuable tree of commerce in the home timber market. This particular tree was bought by one David Gray, cartwright in Aberdeen, who made of it sides 2 feet deep in one piece for traction- engine waggons. We carted trees from all the hills around to Paterson’s mill at Craigcluny, near the new Invercauld Bridge. On the road to Keiloch Farm there, at one time the Home Farm or Demesne of Invercauld, an Englishman was driving the first traction-engine in this district past a huge boulder that lies hard by the road. He struck the boulder with a waggon wheel, and. perforce, had to stop. Full of wrath, he shouted with a shrill voice and strange English accent, “ Who put that stone there? We stabled our horses at the farm, and I just wonder if there are still as many and as big rats there as used to gnaw a road into our corn bins. The year 1884 at Braemar opened with a disastrous gale. Our hut was situated in a gravel pit, and its roof was just on a level with the top of the bank, which was studded with huge trees. My squad and I were in bed, two in a bunk, and the two bunks were placed one just above the other. Suddenly a tree was blown over. and fell athwart our hut. driving a stout limb through the roof and pinning down the blankets between the two men in the top bunk. One was an Aberdonian, and one a Highlandman. Quoth the Aberdonian in dismay: “ A think, Donal’. we wad better rise.” “ Why rise ? “ answered the Highlandman, “ she might as well be kilt in her bet as out off it.”

Our housing problems were quickly solved in those days. Many a time have I seen trees transformed into houses within one week. The outer wall consisted of overlapped wood, five-eighths of an inch thick. The inside wall, or lining, was three-eighths of an inch thick, and we filled the intervening space with sawdust. The fireplace was of brick and clay, and fitted in to the wooden frame. The wooden walls quickly dried and our hut was often too warm. If cracks appeared, we lined the interior with grey paper. Many a hard-working lumberman has lived for years in such a hut with his wife and children. And it is still being done.

A word now about the price of timber. Dr. Keith, in his “ Survey of Aberdeenshire,” 1811, said: “ In 1772, wood from Lord Fife’s estate in Braemar, of the finest quality, was bought at 4d. per cubic foot on the spot. After being floated down the Dee to Aberdeen, it was sold in retail at 8d. Now (1811) it is sold in the forest from 1s. to 1s. 4d., and from 2s. to 2s. 6d. at Aber- deen. Ash, in 1770, was sold at 6d., and is not now below 4s. per cubic foot.” In 1924 the price of the best thick cut of fir is about 2s. 3d., the same as in 1811, and for ash, 2s. 4d. The price in 1811 would have been much inflated by the Napoleonic Wars just as in the recent Great War, when ash soared to 6s. per cubic foot. The timber market is a “ kittle “ business, for after a heavy gale the price may fall away almost to nothing. For example, before the gale of 1894 the whole timber upon the estate of Ruthven in Forfarshire was valued by Patersons for an incoming laird at £9,000. After the gale I purchased the lot, blown and standing alike , for £1,305. From this estate I sold sleepers, delivered in Glasgow, at 11d. each, as compared with to-day’s price of about 5s. For five years after 1894 the market could not use the supply of home timber, and I had two years’ sawing on Fettemear for £500, for much of it was already rotting. Then the price of 100 short pit sleepers fell to 9s., delivered at the pits. We dried them bone dry (before dispatching), to save cost in rail transit.

The fir on Upper Deeside is as fine as any that I know, by reason of its slow growth and closeness of texture. Mr. Burns, who built the wooden bridge over the Don at Parkhill for the first turnpike road to Oldmeldrum, used wood from Braemar .The seats of Newhills Kirk (1820) are of Glen Tanar fir, and still look very substantial. Wheels, which are usually made of hardwood (elm, ash, beech, oak), have been successfully made of Glen Tanar fir, naves, felloes, and spokes. There is nothing to equal lnvercauld larch, and in contracts it is a common habit to specify “Deeside” timber.

For all the trials of the timber trade one needed a strong arm and a stout heart. The days were long and filled with strenuous labour; and were followed by no compensation of home comforts in the wooden hut. A backwoodsman’s besetting sin, if he has one more than another, is a weakness for strong waters and playing cards, especially “Bawbee Nap.” I can remember playing one very wet day for twelve solid hours, and all for one halfpenny of profit. And yet there are very few practical woodsmen who would prefer lodgings to bothy life. For woodsmen are the very best of comrades, sincerely honest and upright. A certain woodsman once set off three miles to a village on Christmas Eve to fetch a “greybeard” of whisky for the squad. He had also to bring new horse reins. The road was ice-bound, with a few inches of snow on top. The man succeeded in reaching the village with the empty “greybeard” intact, but somehow the road seemed even more slippery on the return, and a fall would have been a catastrophe. “Wullie” stood up and considered. Undoing the reins, he tied them end to end, making about 30 feet of a line. Then he tied one end to the “greybeard,” took the other over his shoulder, and set off, gently towing the “greybeard” over the soft snow. On the approach of traffic, he pulled in the jar hand over hand and, the danger well passed, set off once more. In this way a Merry Christmas was secured in days when a Ministry of Transport was unheard of.

One more story, and this (for me) very difficult contract will be finished. A certain woodsman was a good fiddler, and much in demand for weddings, mostly “ barn” weddings. Thanks to real Deeside hospitality, he once had to be put to bed in the straw shed, and awoke therein about nine next morning. He made his way to the kitchen, where the goodwife asked him how he was feeling. “ Oh, just so-so,” was the reply. The good-wife disappeared and soon returned with a glass of whisky, being careful to state that this was all that was left. “Was that a’?” exclaimed Wullie, “ And had a’body plenty?” “Oh, aye I A’body had eneuch,” answered the goodwife. Wullie looked carefully at his glass for a minute, and then with mock anxiety said : “ A sav. Mrs. Davidson, was’t nae awfa’ neat coontit?”

P.S. During the War, certain Canadians were employed cutting timber in Britain. I understand that they were not really trained lumbermen, but a mixed lot of convalescent soldiers. Certainly their work could in no respect be compared with the work of our home trained men.